Understanding Token #3 (Part 1/2): Maker (MKR)

Understanding the Maker Protocol and its Success

Today, I’m going to look into Maker, a decentralized synthetic borrowing protocol on the Ethereum Blockchain.

A note: Maker is the name of the protocol. MKR is the name of the token. MakerDAO refers to the name of the community governing the Maker protocol.

This post is very long, so it’ll be split into two parts and this is part of 1 of 2.

Stay tuned for part 2, where I cover token use cases, and the overall Tokenomics, with a presentation of revenues and costs as well as some of my final overall thoughts.

Part 2 will be dropping on Thursday, June 10th.

TL;DR: The Maker Protocol issues one of the most important cryptoassets: the Dai Stablecoin. Maker charges interest for borrowing Dai without having to pay depositors any interest! Dai has a large volume and is deeply entrenched in DeFi, contributing to Maker’s future success. Stay tuned for Part 2 with a deep-dive into the Tokenomics.

First in “Understanding the Maker Protocol”, we cover the Maker Protocol and understand what Dai is and how users deposit assets to borrow Dai. We then cover Maker’s risk mechanisms and explain how Dai is worth $1.

We go on in “How Successful is Maker?” to look at the success of the protocol and compare it to some of its competitors and think about why Maker is successful.

Understanding the Maker Protocol

Maker is similar to Aave in many ways. Users can use both to borrow money. In my previous post on Aave, there are 2 sections that are worth revisiting before reading this article: “Explaining Depositing & Lending” and “Collateralization & Liquidation”.

Maker is incredibly important as it generates a synthetic asset: Dai (or DAI).

Explaining DAI and Synthetic Assets:

Dai is a synthetic crypto stablecoin. Let’s break that down.

Dai is synthetic because it is created by the Maker protocol.

Dai is a crypto asset because Maker is a decentralized protocol on the Ethereum blockchain.

Dai is a stablecoin because it is always worth $1 (or at least tries to be).

Looking at the graph below, it has been very close to being worth $1 throughout its history and has actually had more variance to the upside than the downside!

This is pretty nice. If someone gave you an asset and told you “Hey this should be worth $1 most of the time” and it turns out that sometimes it was worth $1.01 or $1.02, that’s not really a problem.

The above was a quick summary and I’ll later discuss more clearly: how and when

The Maker Protocol creates Dai

Dai is consistently worth $1 when most other crypto-assets wildly vary in price

Explaining Depositing & Borrowing

Much like Aave, in order to borrow, a user has to deposit some assets first.

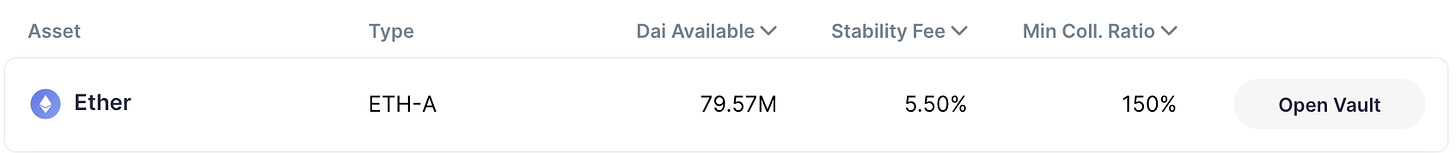

In the above example, there’s an ETH-A vault. You can deposit Ether, open an ETH-A vault, and borrow Dai: up to 79.57M (Dai Available), at a 5.50% interest rate (stability fee), as long as the value of Ether is >150% of the Dai borrowed (Min Coll. Ratio).

Maker, like Aave, also operates as an over-collaterized lender.

However, past this, there are key differences.

Depositing Interest Rates

Maker pays depositors no interest on deposits.

Borrowing Assets

Users can only borrow one asset: Dai

Now, remember how I said the Maker protocol creates Dai? That’s the reason why Maker pays depositors no interest on deposits. Users are borrowing an asset that the Maker protocol itself is creating—consequently, why would they receive any interest? They’re borrowing Dai from the protocol, not from other users lending it out. Maker never lends out any of the collateral users deposit, such as ETH.

What Determines the Borrowing Interest Rates?

MakerDAO, the governance community in charge of the Maker protocol, determines interest rates.

Peg Stability Module (PSM)

For a specific type of collateral, the USD Coin1, which is issued by CENTRE2 and backed 1:1 by dollars in a bank, Maker has an alternate mechanism to issue Dai.

Since USDC does not vary in value, users can deposit 1.01 USDC to get 1 Dai, with an extra benefit of paying no interest.

Instead, users pay a small fee to turn the USDC into Dai and also when they return the Dai to receive their USDC back.

This mechanism is known as the Peg Stability Module or the PSM for short.

Dai Savings Rate (DSR)

Here’s a resource you can read on the DSR.

Tl;dr: You can lock up your Dai and get interest paid in Dai.

In my opinion, this is not important or interesting so I’m glossing over it.

Collateralization & Liquidation

Like other borrowing platforms, Maker enforces a liquidation threshold.3

In the above vault, the minimum collateral ratio is 175%. That means, if at any time, the value of your Ether is under 175% of the Dai you took out, your Ether will be taken and liquidated.

Liquidation Process4

Liquidations are not actually instantaneous. Instead, “Keepers” monitor vaults and if a borrower falls below their minimum collateral ratio, they send the borrowers proceedings to a liquidation auction. In return for this work, the Maker protocol compensates the Keepers with Dai.

The liquidation auction functions as a Dutch Auction.5 The price for the asset, denominated in Dai, starts high, and goes lower over time.

Let’s look at an example6:

A borrower puts in 2.71 ETH into the ETH-A vault and borrows 5,031 Dai.

The ETH-A vault has a 150% minimum collateral ratio.

Minimum Price Needed: 5,031 (Dai Borrowed) * 1.50 (Min Coll Ratio) = 2.71 Eth (Amount Used as Collateral)

Solving for 1 Eth = 2,785 DaiUsing the variables above, we see if ETH falls below 2,785 Dai, the liquidation process will start.

This happened and the collateral was seized and a 13% liquidation penalty was applied. The liquidation penalty in Maker is interesting and we will discuss this later in the revenue section.

5,031 Dai (original amount borrowed) * 1.13 (liquidation penalty) = 5,685 DaiNow since the liquidation penalty was 13%, the protocol needed to recover 5,685 Dai. Eventually, a buyer came along, and bought the ETH at a price of $2,597.

In summary, the protocol recovered the 5,031 Dai it issued, took in an extra 654 Dai as a liquidation penalty, and the liquidator received 2.1892 Eth at a price of 2597 Dai per ETH as this was their bid. Since the borrower originally put in 2.71 ETH, the remaining 0.52 ETH is still theirs.

The 1 DAI: $1 Dollar Peg

Any discussion of understanding Maker also needs to look at and answer one of the most important questions around stablecoins: What makes them stable? In a world where crypto-assets vary in price by 50%+ in a day, how can an asset remain at $1 in value for years consistently?

In short, for Dai: Because it’s backed by assets.

Drilling deep, there are several reasons:

PSM

Given that USDC can be obtained from Coinbase by depositing USD from a bank account, if Dai is to ever exceed $1.00 in value, users can easily obtain USDC, mint some Dai through the PSM, and sell it for above $1 until it comes down to $1.

Liquidation Mechanism

Going to back my earlier section, “Liquidation Process”, fundamentally, the value of Dai comes from it being backed by assets with value.

The liquidations are crucial to this process—if the collateral backing the Dai is no longer valuable enough, the collateral is seized and the liquidation penalty applied as an incentive for all borrowers to maintain their collateral ratios above the minimum.

Emergency Shutdown

In extreme black swan events, such as extreme price swings or a hack, the protocol has an in-built shutdown protocol.7

If this process is triggered, vault owners can withdraw their excess collateral first. Afterwards, Dai holders can exchange their Dai for the remaining collateral proportionately.

A simplified example:

Let’s say there’s 1 owner of a vault with 1.5 ETH deposited and 3000 Dai borrowed.

After borrowing the 3000 Dai, the vault owner exchanged it for some NFT art and no longer owns it.

The shutdown occurs.

If the price of ETH is $2800, only ~1.07 ETH is needed to cover this. The vault owner gets to keep their 0.43 ETH and the holder of Dai is entitled to the remaining 1.07 ETH.

This is the end of the protocol mechanisms by which DAI maintains a peg, but there are a few other reasons:

Faith / Lindy Effect

The Lindy effect, from Wikipedia8:

The Lindy effect is a theorized phenomenon by which the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things, like a technology or an idea, is proportional to their current age.

Essentially, because Dai has been around and it has held its peg, it’s expected to keep maintaining its peg. And furthermore, the longer it keeps its peg, the longer it’s expected to keep maintaining its peg.

In more normal english: If billions of dollars have been spent transacting with Dai over several years, don’t you think it’s pretty likely that it continues to be worth $1?

Liquidity

No, not liquidations, but liquidity. There are several deep pools of capital for swapping USDC or other US dollar stablecoins for Dai at a 1:1 rate. Outside of the Maker protocol and its own mechanisms, several people have committed hundreds of millions of capital to the belief Dai is worth $1 and you can take them up on their offer.

In fact, outside of the PSM, you can swap $250 million worth of USDC for Dai, at only a 0.24% cost. This particular liquidity is provided by pools found at automated market maker (AMM) protocols Uniswap and Curve.

How successful is Maker?

Maker is one of the oldest Ethereum protocols and represents a significant amount borrowed.

It’s often compared with Aave and Compound, as the other 2 represent the largest lending protocols, but these aren’t 1:1 comparisons.

Aave and Compound lend out user-deposited assets, whereas Maker, as covered before, mints its own asset, Dai, to lend out.

Thus, if we are going to compare the 3 protocols, a fair comparison metric might be total amount borrowed:

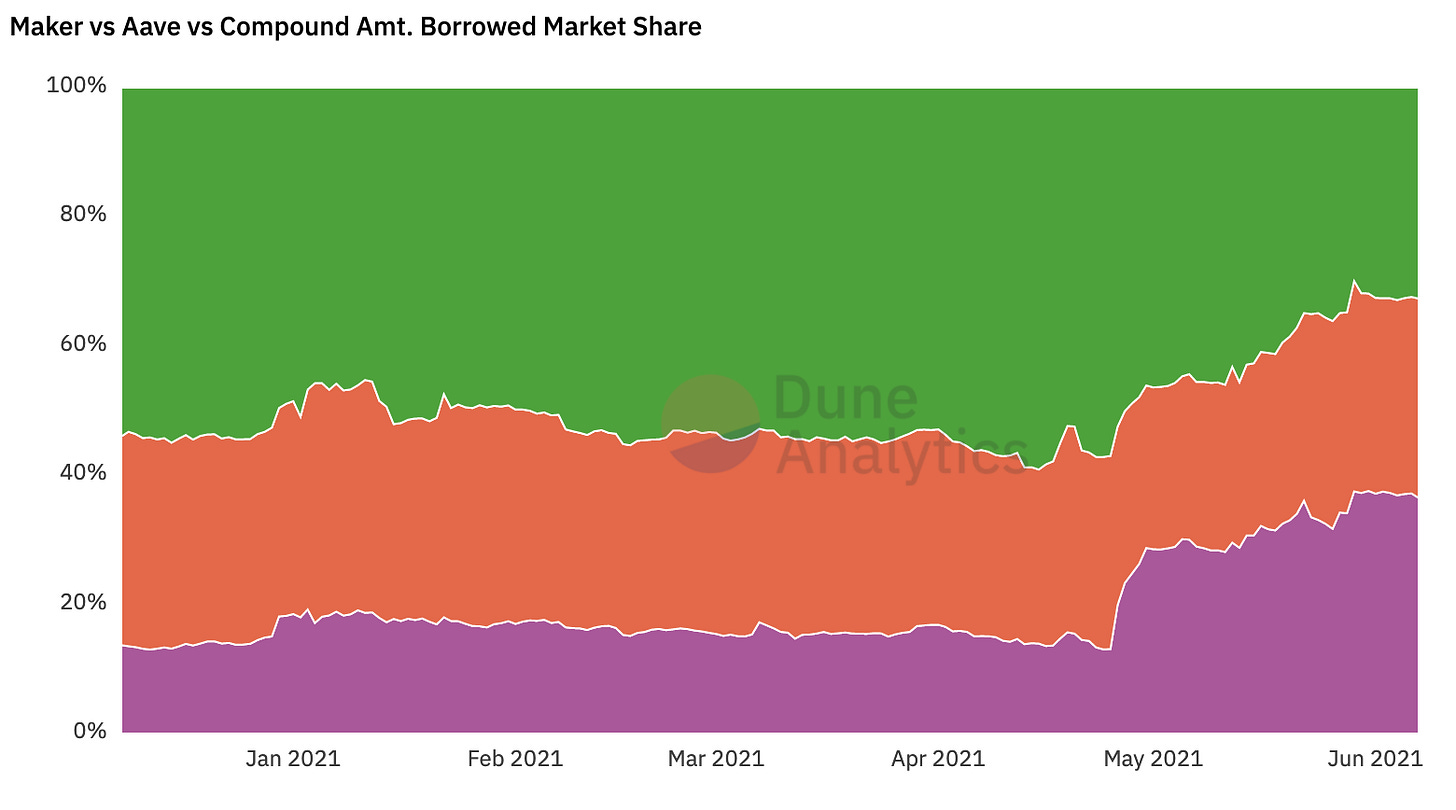

Maker has held a pretty consistent market share at around 1/3.

But keep in mind, the above only represents Ethereum. Aave is on Polygon and well over $4B is borrowed there, nearly doubling Aave’s amount lent out.

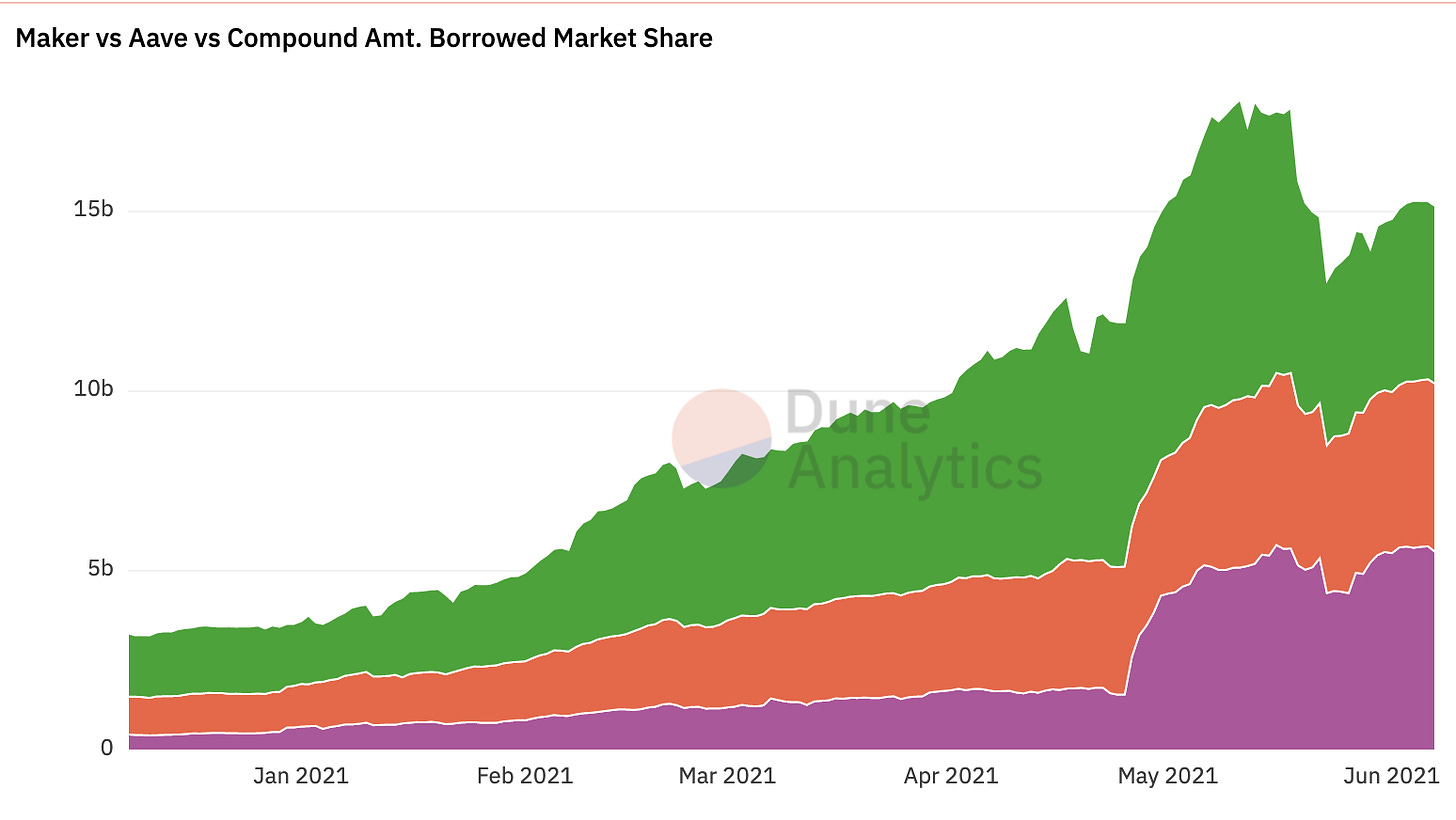

If we are to just look at Maker’s total volume lent out over time, in the above image, we see pretty steady growth until recently. This is after the early May crypto crash, where ETH crashed ~60%, wiping out a lot of borrowers.

Looking at a slightly different chart, we see the Dai crash was actually not that bad and is well on its way to recovering. However, the amounts are also different. How can total Dai be so different from borrowing volume? Simple, because Dai minted through the PSM does not count as “borrowed” Dai. We can see an interesting trend here: After the crash, most of the Dai minted has been through the PSM and not through borrowing by depositing assets into a vault.

Network Effects

Dai is deeply entrenched in DeFi. Several other protocols utilize Dai in fundamental ways.

Compound & Aave: Yes, they’re technically competitors, but both Aave and Compound hold a ton of Dai!

Compound:

Amount Deposited: $3B+

Amount Borrowed: $2.5B+

Aave:

Amount Deposited: $2.4B+

Amount Borrowed: $1.8B+

AMMs: Between Uniswap, Curve, and others, there’s well over 200M Dai inside of liquidity pools.

Yearn9, which is a decentralized investment fund, has several vaults where users can deposit assets, and the Yearn protocol will invest them in various strategies to compound the asset. The largest vault is Dai, with nearly $600M locked inside. Several other Yearn vaults, such as an ETH vault, rely on locking up ETH in a Maker vault, borrowing Dai, and investing the Dai. Thus, the total amount of Dai used by Yearn is actually higher.

Keep in mind the above numbers can add up to more than the total amount of Dai. That might sound weird, but it’s because each protocol can claim it “holds” the same Dai. For example, I invest 1 Dai into Yearn which lends it out on Compound. Thus, both Yearn and Compound can claim they “have” 1 Dai.

If that example still doesn’t make sense, let’s think of a TradFi example. You give your $2M to an advisor who invests it in Vanguard Index Funds. Vanguard gets to say they’re managing $2M, your advisor gets to claim they’re managing $2M, and you get to say you have $2M. Each claim is individually correct, but if you added it up all, the same $2M got counted three times! The same thing can happen in Crypto and no one is lying or misleading—the technical word to use for both is different. Yearn manages and invests money, Compound lends money, and the original investor, you, owns the money.

The more entrenched DAI is in the DeFi ecosystem, the stronger the demand, and thus we have a virtuous cycle leading to more DAI growth.

What about other Lenders?

I already said a few things comparing Maker to Compound & Aave. I’ll have more to say in the Tokenomics section.

We can also compare Maker to a very direct competitor, Liquity, which locks up collateral and mints a synthetic stablecoin, LUSD, also pegged to $1.

Liquity offers some unique advantages:

Lower Collateral Ratios: Borrow against Eth with as little as 110% minimum collateral ratio.

No interest payments: A big differentiator.

Liquity is off to a strong start with $2.65B ETH locked and $750M+ LUSD minted.

It’ll be hard to overcome Maker Dai’s network effects, but Liquity is off to a strong start. They’re offering an innovative new product with high-value differentiation.

Summary

In short, the Maker Protocol is extremely successful. Looking at only the Total Value Locked (TVL) in the vaults is not the primary metric I’d examine. Instead, I’d look at Total Dai which represents the demand for a decentralized stablecoin and the DeFi entrenchment which increases the network effect value of the Maker Protocol.

I would love to hear your thoughts and please stay tuned for part 2, where I cover token use cases, and the overall Tokenomics, with a presentation of revenues and costs as well as some of my final overall thoughts.

Part 2 will be dropping on Thursday, June 10th. Subscribe to not miss it.

You can find me on Twitter @AishvarR or reach out to me at raishvar@gmail.com.

Personal Disclosure: I own a small amount of MKR.

CENTRE is a consortium backed by Circle and Coinbase. More details can be found here.

Read the “Collateralization & Liquidation” section of my previous post on Aave to understand this terminology.

Here is the in-depth methodology behind the Liquidation Module: https://docs.makerdao.com/smart-contract-modules/dog-and-clipper-detailed-documentation

To give an example of a Dutch Auction, take a watch that starts at $10,000. No one wants to buy it at $10,000 so the price drops $100 every minute. Finally at $8,000, someone decides to buy it and the auction concludes. This has the advantage of the winner knowing the moment they decide to bid, they will win the auction.

This is an actual liquidation example, found here: https://makerburn.com/#/liquidations/eth/173

Yearn is an extremely fascinating protocol that I intend to cover in the future.

Great post! I still wonder about the core question though, Why would people want to stake the crypto for DAI? What can they do with the DAI that they cannot do with crypto? One use case I see is to potentially profit from a predictable spike in the value of crypto.